In part two, Scott discussed in detail on how he became a fencing coach, building upon his foundation to seek out mentors and master coaches from home to abroad. Since the release of Part 1 last month, Scott has also received his Level 3 accreditation from Australian Fencing Federation.

Ed: Firstly, congrats on your level 3 accreditation for coaching. Can you tell me what Level 3 accreditation entails and how is it different from level 2?

Scott: The way it works in the Australian system is that there are 3 levels:

- Level 1 is equivalent to a club coach

- Level 2 is a state or province coach, and

- Level 3 is the equivalent of an international coach

If there is a big step between 1 and 2, there is an even bigger step between 2 and 3 and rightly so, as it should be regarded as a qualification of the highest standard. In terms of getting a level 3, you have to apply through recognition of prior learning as there isn’t a level 3 course in Australia. The entire system got broken down and restructured around covid, though in the past you had to attend an FIE course or similar, attend an Olympic solidarity course and travel as part of an Australian overseas team. These are the things that I did plus a lot more. The new criteria for each of the levels are now available on the AFF website, though I wouldn’t be surprised if things are updated again by the new national coaches coming through this year.

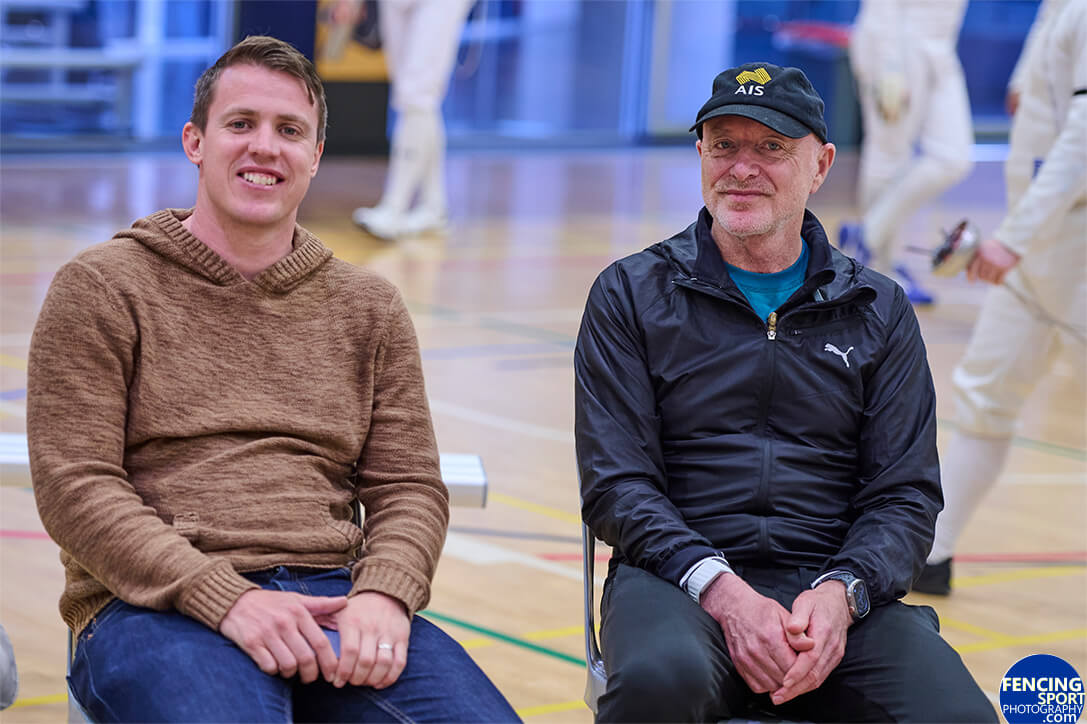

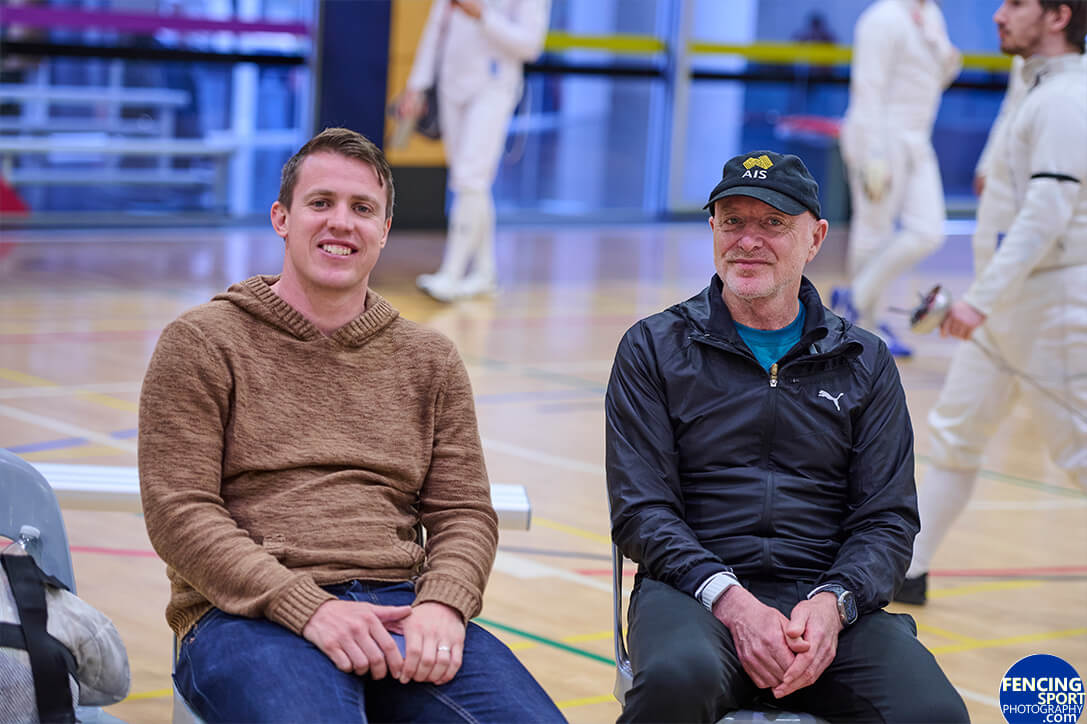

Scott and Gerry Adams from VRI Fencing Club.

at 2024/25 Robyn Chaplin Memorial Tournament – (AFC#3)

Contributor: Scott Rawlins (Australian Epee coach from University of Western Australia Fencing Club / Level 3 accred.)

Producer / Photographer: Ed Chiu

Date: Feb 2025

All the photos (except first photo) in this post are supplied by Scott.

Ed: So it’s good that we are having overseas coaches in Australia or in your experience that you learn how to coach in Hungary. How did you manage to have that opportunity? But obviously your primary goal is to coach so I understand you would go overseas to learn. Did you do some research on how coaching is done in Australia before learning how to coach in Hungary?

Scott: I did a lot of work before I went to learn overseas, but my learning opportunities were limited as there is not much coaching education in Australia and Perth. So, I studied for a master degree in sports science, read a lot of fencing books, which I still do, and learned to give private lessons by copying lessons from other coaches.

One issue I had though is I didn’t feel I was working within a comprehensive system when I was coaching, so to see my future mentor Gerry Adams give a Hungarian style lesson just blew me away. Fortunately the coach who had the greatest influence on him, Gabor Udvarhelyi had a video about his coaching system on YouTube so I studied that a fair bit.

Scott with the other students and instructors at the FIE Academy.

As fate would have it my first international competition was in Hungary so I took the opportunity to train at Udvarhelyi’s club, MTK.

Scott continues: I had the opportunity to work with Dani Bojti, one of the club coaches. I would do a series of lessons with him as an athlete for a couple of weeks, come back to Australia to copy and practise the lessons as a coach for a year, then go back to Hungary and ask him what to do next. I did this basically every year for the next few years.

The problem I had though was that although I was starting to understand the system I was only seeing parts of it and my delivery wasn’t very polished so I made contact again with Gerry and started working with him as a mentor and put together lesson plans. Even though he was living in a different state I would record my lessons and he would give me feedback over Zoom. I was still aware of my shortcomings as a coach though, particularly in aspects such as group lessons, the pedagogy of working with children and terminology, so I realised it was time to bite the bullet and find my way back to Hungary again to learn at the FIE Academy.

Scott at his work experience at MTK with coaches (L-R) Johan Lewin, myself, Gabor Hadalin, Dani Bojti, Dávid Nagy

Scott: The coach there, György ‘Cefi’ Felletár did an amazing job in straightening me out and filling in the gaps I had, and after finishing the course I was able to answer all of the questions I’d had circling around in my head for years but no one seemed to be able to answer in Australia. I really enjoyed working with Cefi, he had such a deep understanding of fencing and made it fun. In addition to attending the course I was also very lucky to arrange work experience at MTK, teaching every day for 3 months at a world class club, working from the ground up and seeing how Dani worked with children right from the very start. I was able to take a lot from the academy and work experience, but I wouldn’t have been able to soak it up so well without the preparation I put in beforehand.

Ed: It is admirable that you have the perseverance and persistence to get to the core of teaching, learning and continuously improving your skills in fencing and as you mentioned there was a lack of solid resources in Australia. Not many people have that energy or willingness to get to the depth especially when things are out of reach.

Scott: To me it has been a necessity. When I was a younger coach, a master gave me the best advice he was ever given, and it was also the best advice I’ve ever received – “as a young and up and coming coach, you’re going to waste a lot of talent!” He elaborated that what he meant was that unless you are a master coach, particularly in the private lesson, you are going to be teaching students bad habits. I was already working professionally as a coach and my thought was that I might not be a master coach, but I could put things in place for quality control to not ‘waste talent’ and damage students.

Scott with the coach of the FIE academy, György Felletár

Scott: The first was to work within a system – I cook at home and even though I’m not a chef, as long as I follow the recipe, I’ll end up with something that looks like what it shows in the picture. It’s like that when I give private lessons and group lessons – I follow certain lesson themes in a certain order with a teaching pedagogy that is the same as what I learned at MTK. Hopefully my fencers come out looking like the fencers over there!

The second was to have someone above me, a mentor in case I start to make mistakes or go down the wrong path. There is a great saying I once heard “No fencing master should be so arrogant that they should not ask another fencing master to watch one of their lessons at least once a year”.

You also have to constantly be working on your professional development, firstly to improve your skills and secondly to stay up to date with modern trends.

Scott continues: Besides coaching courses (I have done some great ones with the incomparable Maestro Enrico Di Ciolo), books are also fantastic and I think any aspiring coach needs to read a lot. Unfortunately a lot of the classics are out of print these days but if you look around you can find them after a while online for an affordable price.

Classics that I recommend include “Fencing and the master” by Laszlo Szabo and “Fencing: The Modern International Style” by Istvan Lukovich. Finally I always work hard to practice and improve my teaching. It’s a bit of a generalisation but they say it’s 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to achieve mastery. That’s 40 hours a week for 5 years, or 20 hours a week for 10 years if you want to become a master. Done in the right way of course.

Ed: In photography, French master photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson once said ‘Your first 10,000 photos are your worst’. With the 10,000 photos, you have all this time to refine your skills, research, explore, experiment, learn from different masters. In the good old days, we were required to study photography in universities before getting a paid job in the photography industry, the standard and expectation was high. We would start off as an assistant for up to 3 years some people had apprenticeships before becoming a junior then after another 5 years you are a senior photographer, by this time photographers usually have a specialisation. Each step of the way you gain more experiences and technical knowledge among other things. It took me 12 years to become the Head of photography for Australia’s giant ecommerce group in 2012.

By the time I began shooting fencing and sport photography in 2022, I’ve already photographed many lots of 10,000 photos, and proficient with associated disciplines that make up the work. Most photographers probably don’t have this opportunity because some things can only be a ‘work in progress’ if you work in the industry and when you’re getting paid to do the job you have to meet the demands. It is becoming a harder industry to enter since the last 3 years, while it is not impossible, but photographers need to know a lot more than just clicking the shutter. I shoot daily because it has been my profession for 25 yrs full time. No two days are the same, I would discover something new also I work when I’m on vacation at anywhere in the world. I treat Photography like an investment and a lifestyle, not so much as a job anymore.

Soctt undertaking his FIE Coaching exam at FIE Academy.

Ed: What was your take away from studying Master of Sport Science degree in relation to fencing? I have met a few fitness trainers with this type of degree, with a greater understanding of how the body works than the general fitness trainers one would find in any generic gyms. My personal trainer for strength and conditioning has a degree in sport science in Human Movement, he has in depth knowledge of body movement and mobility, on top of that he plays footy and I think as a sportsman with practical skills along with his knowledge, it works well when working with people like myself in fencing and gives me exercise each session to support that.

Scott: Firstly let’s remember that sports science is a huge field – there is psychology, physiology, nutrition, pedagogy, biomechanics, exercise programming, just to name a few! I accept that in Australia the degree doesn’t really improve my employability in terms of fencing coaching but when we spoke before about the different aspects as a coach, a sports science degree fills in a huge amount of the gaps and gives you much more depth.

It also helps you to justify your methods – if I teach in a certain way and someone asks me why, I can explain in a scientific way. That gives me and my students confidence that what I am doing is pedagogically and scientifically sound. It also helps me to further develop my skills and understanding by myself because although in university you learn knowledge, more importantly it teaches how and where to seek out the knowledge you need in a scientific way. These days on the internet a lot of knowledge and information is available to pretty much everyone, but you still have to train yourself to critically analyse and understand it. I definitely subscribe to the notion that knowledge should be available for everyone, but in order to understand and use it, that’s a skill that has to be earned through guidance and practice.

Scott celebrating on the podium with some of the kids he helped to teach at MTK. They were only U13 but Scott helped train 2 Hungarian National champions.

[2023, Hungarian National U13 championships]

Ed: Once you have learned the Hungarian style of teaching / coaching, is it hard to switch to another style? But also one fencer takes up a different style and fencing seems to be more universal and people are sharing and style of fencing.

Scott: I would say that good fencing is good fencing, whether it is French, Italian, Hungarian, Polish etc. With the world becoming more connected with travel we are closer to getting a modern international style of fencing but such things as schools still exist, because of the national academies that produce students in different parts of the world.

A fencing school is defined by a coaching philosophy and the fencer is a manifestation of that philosophy – think of how precise French fencers are, or how energetic Italian fencers are for example. Some styles of fencing are quite compatible with each other and some are less so. It’s also never a good idea to mix fencing styles as a coach or you can end up with a Frankenstein’s monster! In other words, a skillset that isn’t complete and doesn’t compliment itself.

The philosophy of the Hungarian system, at least the way I see it, is that the teacher has to teach the student everything, and the student has to be smart enough to decide what to use for themselves. In this way the Hungarian system I believe is very special, because it is so comprehensive and covers a lot of material that you find in other systems. I would like to think one of my students could go to any other coach in the world and take a decent lesson. Once the student’s technique and understanding has been established that can also be a positive thing as they can learn different actions that might suit them or see things from a different perspective, even if that new perspective is how to counteract that system or justify what you already do. Having said all of this, if you have a fencing master, you should stick with them, or find another master who is similar. It doesn’t matter what system you are in, if you see a student who changes to a master in a different system, the results are usually never as good.

Reading as recommended by Scott:

Fencing and the master by Laszlo Szabo

Click here to read Part 1 of this interview

Leave a Comment: